Bala Sole – Visages

Bala Sole – Visages

October 24, 2013

Ailey Citigroup Theater

Young dancers who set out on the journey toward a performance career learn early on that the dance world can be a cruel place which excludes many whose hearts are full of love for the art and whose commitment to their work is fierce. When a young dancer stands before the gatekeepers of dance companies and conservatories, they soon find out that their heart and commitment will only carry them so far, especially if they’re a very tall girl, or a short man, or flat footed, or curvy, or a person of color, or someone north of age thirty.

When discouraged, overlooked and rejected by the gatekeepers due to his height and his age, BalaSole Artistic Director Roberto Villanueva circumvented the obstacles. Not only did he choose to start his own company, but he decided to focus his company’s mission on providing a stage for those whom the dance world is quick to silence. At the end of the evening, when his company of ten stood shoulder to shoulder to take their bows, it was evident that very few of them resembled one another. Their program, Visages, showcased a variety of solos created by dancers who were celebrating the very traits that might have otherwise marginalized them in another dance company.

The company danced Chapter 10 to open the program. It’s a short piece set to music by Haydn. It opens with the dancers lined up from downstage to upstage. They alternately step out of the line and look back at those standing in the line. To me, this seemed to celebrate their defiance of the exclusionary rules of dance. They seemed to look at one another with delight, to celebrate that they were working in an atmosphere which sanctioned their differences.

Dressed in black leotards, they perform phrases with pretty ballet elements, woven together with modern contractions and sharp port des bras which lift and open the chest, as if the individuals are embracing possibilities. It’s in the unison passages that we can see the variety of expressions with which steps can be executed. The dance was created and rehearsed over the course of six days, as a method for the dancers to “get to know one another”.

Falling Together, Falling Apart seemed like a valiant battle against gravity, choreographed by Teal Darkenwald and danced with strong emotion by Christa Hines. She rises gracefully from the floor as if lead by her outstretched hand. She seems stricken as she turns on the floor before sailing with ease into a standing turn. The entire piece seems like an act of determination to triumph above the pull of troubles, setbacks or enemies. We feel her frustration as she pounds on the floor, yet she seems uplifted and especially expressive when executing lush port des bras phrases.

Sining has a lovely Japanese atmosphere. The piece was choreographed and performed by Janina Clark, danced to Sakura performed on koto. Ms. Clark is a beautiful dancer, and her movement is so clean as her arms twist and flutter, and she strikes poses that we may have seen in traditional Japanese artwork.

I especially loved Revealed, danced and choreographed by Steven E. Brown, who (like me) is 56 years old. The movement of his piece reminded me of some of the work that I’ve seen done by Eiko and Koma. Brown works very slowly, mostly above the waist, his focus on the smallest details of the movement rather than on big sweeping gestures and bravura. From beginning to end, the dance travels about five feet, yet it takes us on a journey of controlled strength. It isn’t until the final moments of the dance that Brown shows his face directly to the audience, while rising up on releve. For me, this piece seemed to illustrate the need for companies with a mission like BalaSole’s, and the reasons why a dance career needn’t end while the dancer is still young.

I’ve seen Ursula Verduzco’s Nothing to Hide several times in the past year. The piece is malleable and it seems to tell different aspects of the story with each performance. For me, this performance was the most powerful one yet, packing the deepest emotion. Ms. Verduzco’s movement seemed especially lovely, especially controlled, especially lyrical. Her arms are beautiful and expressive. There are a few moments when she seems to be struggling to take a stand or to find her voice, but she is shut down, usually by her own will. It is only in the last moment of the dance that she finally opens her mouth wide. I was taken by the look on her face — a combination of strangling fear and defiant determination to move ahead, to move beyond the fear.

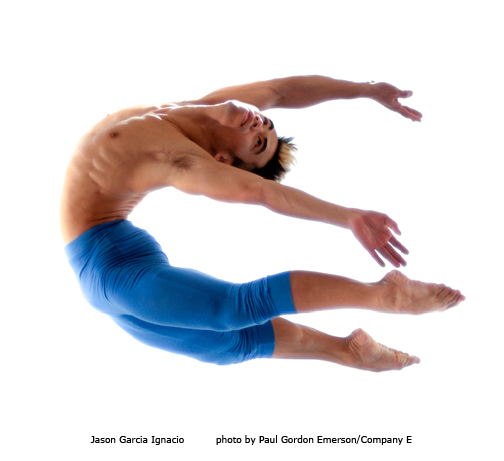

Jason Garcia Ignacio choreographed and performed My Brother’s Keeper to music by Couperin. Mr. Ignacio is so exciting to watch. He has fierce strength, great control and a very supple back. The first section of this piece plays with contemporary movement against the steadiness of the baroque accompaniment. The second section seems to take its lead from the music. At moments Ignacio seems to travel with an invisible partner. The dance winds up where it began, only this time Ignacio looks sharply to his right in the moment before the blackout, as if acknowledging another presence in the dance.

Sensational flamenco vocalist Julia Patinella sang a capella for Go To The Limits of Your Longing. Dancer and choreographer Anna Brown Massey is seated opposite her. Compared with the tremendous emotion exuded by Patinella, Ms. Massey’s movement is compact, smaller, and limited. As with some of the other pieces in the evening, she seems to be demonstrating the restraint imposed by society upon the dancer who wants to explode and take off. As Ms. Patinella rises to her feet, belting our her song, Ms. Massey unfurls her arms and legs with caution and self conscious reserve. She never quite completes her extension, as if deliberately withholding her energy, rather than actually taking the same risks as the vocalist.

Distancia opens with dancer/choreographer Katherine Alvarado confronting the audience directly. Deep in a controlled grand plie, she stares straight at us with an intense focus. But as the violin music fills the air, she seems to drift off into a trance, her long hair cascading, her attention wandering, her head bobbing gently to the side. Perhaps she’s falling into a dream. Her outstretched arm initiates a traveling phrase and then a series of chaine turns. At the end of the dance, she looks around, as if having returned to consciousness and regaining her bearings.

Body Rebellion was a favorite piece of mine. The stage lighting becomes bright white as choreographer and dancer Delphina Parentiv turns on her shoulder and initiates a series of interesting and original phrases. She has the stage presence of a rock star. Her hips are loose and she consistently surprised me by taking the movement further than I’d have expected it go. Her musicality is strong and her phrases join together seamlessly. The closing moments of this piece were especially endearing, as Ms. Parentiv covers her mouth, cocks an ear to hear, then turns an imaginary key to her own heart.

The final solo, Seconds Remain The Same, is choreographed and performed by Artistic Director Roberto Villanueva. Though he said he was 43 and felt as if he was 83, none of that was in evidence when he danced. His stage presence is commanding. Though the piece seemed to be abstract, his strength, control and amazing flexibility seemed to tell a compelling story.

The evening closed with a piece called To Be Determined, which showed some further development upon the opening piece. This time the dance unfolded into a series of trios which teamed together various company members with a wide sweep of ages, builds and styles.

It’s always wonderful to see the work of artists who drive their lances and stake their claims, regardless of what the gatekeepers have to say about them, based only on their physical appearance. In every other culture, all members of the community are encouraged to participate in the dance. It’s good to see this spirit whenever it surfaces in the western world.