Shostakovich Triliogy – American Ballet Theatre

Choreography by Alexei Ratmansky

Metropolitan Opera House – June 3, 2013

American Ballet Theatre’s Shostakovich Trilogy reminded me of everything that I find so attractive in Alexei Ratmansky’s choreography. Though it is intricate, complex and demanding in terms of technique and staging, its humanity is always in evidence. There is always a gesture, large or small, which anyone can recognize as an expression of the human experience. Though his formations and phrases are beautiful on the surface, each one also seems to be laden with deeper meaning or context.

American Ballet Theatre’s Shostakovich Trilogy reminded me of everything that I find so attractive in Alexei Ratmansky’s choreography. Though it is intricate, complex and demanding in terms of technique and staging, its humanity is always in evidence. There is always a gesture, large or small, which anyone can recognize as an expression of the human experience. Though his formations and phrases are beautiful on the surface, each one also seems to be laden with deeper meaning or context.

Dmitri Shostakovich composed Symphony #9 in 1945 to celebrate the Russian victory over Nazi Germany in World War II. Though Ratmansky’s choreography for this piece is well detailed and full of dazzling counterpoint, he captures a carefree feeling in the opening sections. It is delightful to see the way that the dancing picks up on small details and phrases in the music, amplifying them with movement in the arms or feet. In the larger formations, there is often this stunning tension and release. The dancers crowd close together before the dance opens up and their arms and legs unfurl in kaleidoscopic fashion.

In gentler moments of a pas de deux, the dancers pause, no longer focusing on each other, but looking beyond to measure their surroundings. Throughout the dance, several men gather to lift and travel with one dancer. I felt that this really brought out the masculinity, the power and the fraternity of the men.

The closing moments bring the celebration to a climax with an extraordinary ending, which made the audience gasp at its beauty and the surprise it delivered. Principal roles in this performance were danced exquisitely by Veronika Part, Roberto Bolle, Jared Matthews, Stella Abrera and Sasha Radetsky. Praise has to be given to all the dancers in the ensemble sections as well, for their outstanding work.

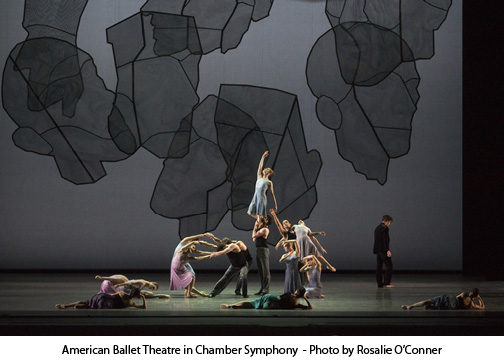

Chamber Symphony is a beautifully haunting dance. When the curtain went up, I felt as if we’d walked in to the middle of a story in process. Dancers are lined up as couples in various stages of pulling apart. A central figure emerges, played with great heart and emotion by James Whiteside. A crowd gathers around him, as if in support or curiosity. When he falls to the ground, they all step back in shock, then withdraw.

Three women, danced superbly by Sarah Lane, Yuriko Kajika and Hee Seo appear to be his muses, somewhat recalling Balanchine’s Apollo. There is a dreamlike quality to the piece. Perhaps the story was unfolding before us. Or maybe tragic events were being recalled from a dreamlike state. Whiteside is bare chested, wearing a suit and skin tone ballet slippers, which from a distance make him appear to be barefoot. He often seems lost and longing or stricken. His muses swoon in his arms or drift away from him.

For Piano Concerto #1, communist imagery of red hammers and sickles hang above the stage against a gray background. The dancers’ unitards are gray in front and red on the back, which create striking patterns as they constantly change direction. The staging and the movement are so complex with few unison phrases. This creates great dramatic effect. At times there is so much happening even within the ensemble dances that it’s hard to know where to look. But the drama and the emotion are maintained at times even with simpler forms, as the dancers move in straight lines or perform wisps of Russian folk dance steps.

The leading men, danced by Danil Simkin and Calvin Royal III, are dressed in gray and their partners, Xiomara Reyes and Gillian Murphy wear red leotards. Their pas de deux sections are lyrical and the lighting is softer and atmospheric. At one moment, when the company returns to the stage, the two women stand still, holding on to each other, each protecting the other, as they take in the sight of the dancers who surround them.

One of the most haunting moments of the dance came as the men crossed the stage on the diagonal, each with a woman balanced on his shoulder, her legs in attitude suggesting the shape of the sickle. Throughout the entire evening, I was taken by the workmanlike posture of the men. They move with urgency, with the physicality of laborers. They wear fixed looks with intense focus, and they often travel together at close quarters in small groups, an assembly of them being used to lift one dancer.

This was a program of exceptional dancing, not only from the principals, but from the entire company. Ratmansky’s creative voice is unique and it works so beautifully on American Ballet Theatre.