Benjamin Briones Ballet – Choreographers Residency and Performance

Steps on Broadway – September 20, 2013

I always look forward to seeing new works by Benjamin Briones, Ursula Verduzco, and the choreographers and dancers with whom they work. Their programs always feature a strong ballet and Latin influence. Their work stands out in a world where technique and tricks are often held in highest esteem. Briones and company present works that focus on reaching the viewer’s heart, and they find a surprising variety of styles and pathways with which to do this.

I always look forward to seeing new works by Benjamin Briones, Ursula Verduzco, and the choreographers and dancers with whom they work. Their programs always feature a strong ballet and Latin influence. Their work stands out in a world where technique and tricks are often held in highest esteem. Briones and company present works that focus on reaching the viewer’s heart, and they find a surprising variety of styles and pathways with which to do this.

The performance took place in the corner studio on the third floor of Steps. When the room was darkened, the night time city became the backdrop, made mystical by the light of the full Harvest Moon. It seemed an appropriate setting for the opening piece, titled All That Remains, choreographed by Briones. Somber and reflective, the dance addresses feelings of loss and loneliness. Six women dressed in gray wander the floor to a classical guitar accompaniment. No one is smiling. From time to time, they cast questioning or wistful glances at one another, or move in unison for a few phrases. Lucia Campoy’s solo is weighted with an undercurrent of heartache as she reaches out or lays her hand over her chest. But in the final section, when the women dance together, they seem resigned to their fate, and there is now a sense of strength emerging alongside their sorrow. The choreography never becomes contrived — it remains elegant and straightforward. In the closing moments of the dance, the women line up and move forward, maybe even as a community, then they suddenly look up in unison for a moment before the blackout. Briones is masterful in his use of small gestures like these, which sing the praises of the human spirit. I appreciate the seamless transitions with which Briones’ choreography suggests the strength and wisdom which can emerge from hardship.

Sarah Rodak danced an excerpt from Vera Huff’s Five Ninas, a suite set to different songs by Nina Simone. For Wild is the Wind, Rodak seems to embody the spirit of love itself blown along on the wind. She is rolled along the floor. She slowly rises, then rides the wind back down to earth. There is a beautiful elemental feel to this piece as the movement swells and subsides. Rodak rises, feet planted on the floor, before being swept up in a gust of chaine turns across the floor, until the dance closes in a dramatic stormy ending. Assistant choreographer Jordan Fife Hunt spoke about stressing the importance of relationship in his work with Huff. As I watched Rodak move, she seemed to personify the elements of a relationship itself, rather than the individuals who were in the relationship.

A Straight Line of Two Circles, choreographed by Felix Aarts, shifts the energy of the program abruptly from the romantic to the abstract. The dancers wear short clear plastic raincoats over their leotards. There is a feeling of unrest as they scurry from side to side or venture upstage with their hands trembling. At times I wondered if they were portraying the frantic and futile “busy-ness” of our society. The movement of the hands are prominently featured. One woman appears to be counting, taking inventory. Another looks as if she’s polishing furniture. Another holds her trembling hand to her forehead, maybe as if to describe a frantic thought process. Aarts said that his intention is to challenge the viewer to come up with their own narrative. I found it surprising that he conceived the dance with the dancers and found the music for it later — he said that he’d changed the music for this piece four days before the performance. He wanted to find music to illustrate the movement, rather than the other way around.

Ursula Verduzco performed her dance Nothing to Hide, which I’d seen and reviewed in different incarnations at various festivals. I’d never before seen her perform the solo herself, so it was remarkable to witness the level of emotion she was able to summon, even though this performance seemed scaled down for the smaller floor, in comparison to earlier ones that included a set. Verduzco’s hair is worn long and sometimes acts as a screen to hide behind, or it flows wildly to symbolize her anguish. She slaps the floor in frustration. She deftly dramatizes the struggle to find one’s voice and to make a statement with it.

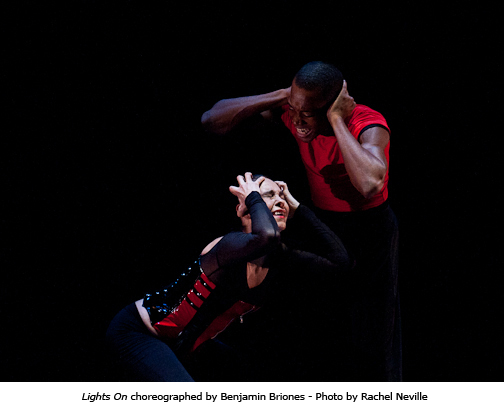

Briones’ Lights On tells the story of a couple who move from love to hostility to remorse and back to love, as if on an endless loop. The red in their costumes seemed to personify the fire of their passions, both destructive and loving. As the lights come up, we see the couple hand in hand, leaning away from each other, pulling apart, until the woman lets go and the man falls to the floor. An argument ensues. She escalates. He outdoes her. Tension builds until she vents her frustration by slapping his face. She knows that she’s gone too far and her remorse is instantaneous. Contrite, she approaches him. Their truce is demonstrated as they dance an electrifying pas de deux. There is strong chemistry between dancers Kara Walsh and Taylor Kindred. Their partnering appears to be effortless, with beautiful ballet technique. But I was most impressed by the sweep of emotions that they were able to conjure, not only with facial expressions and mime, but with the movement of their bodies, with the unfolding of an extended leg, or with the trust of a lift. Again, the expression of Briones’ work moves deftly and invisibly from one emotion to the next, through love to antagonism to regret to reconciliation.

Briones’ Lights On tells the story of a couple who move from love to hostility to remorse and back to love, as if on an endless loop. The red in their costumes seemed to personify the fire of their passions, both destructive and loving. As the lights come up, we see the couple hand in hand, leaning away from each other, pulling apart, until the woman lets go and the man falls to the floor. An argument ensues. She escalates. He outdoes her. Tension builds until she vents her frustration by slapping his face. She knows that she’s gone too far and her remorse is instantaneous. Contrite, she approaches him. Their truce is demonstrated as they dance an electrifying pas de deux. There is strong chemistry between dancers Kara Walsh and Taylor Kindred. Their partnering appears to be effortless, with beautiful ballet technique. But I was most impressed by the sweep of emotions that they were able to conjure, not only with facial expressions and mime, but with the movement of their bodies, with the unfolding of an extended leg, or with the trust of a lift. Again, the expression of Briones’ work moves deftly and invisibly from one emotion to the next, through love to antagonism to regret to reconciliation.

The program closed with Megan Phillipp’s Divided By Three. Verduzco portrayed a woman who seemed to be haunted by two alter egos, danced by Lucia Campoy and Yeong Ju Son. I really liked the compositions that Phillipp created by using formations of three. In a passage where the three women sat in a row of chairs, Verduzco bolts upright in the center, while the dancer to her right sits upside down, head toward the floor and feet reaching up, and the dancer to her left lays her head in Verduzco’s lap, pinning her in place. Or the recurring theme where Verduzco stands at the head of the line and the arms of the other two dancers come out behind her, as if they were her own limbs, holding her back. As tension builds, the accompaniment of a piece by Philip Glass keeps whirling and whirling. I especially loved the purple costumes with tulle skirts which were used for this piece.

The friendliness and hospitality of this company was clear in the way that connected with the audience after the performance. They hosted a Q&A, and seemed genuinely interested in removing the barrier between artist and audience. To elaborate on the words of Jordan Fife Hunt, they acknowledge that the performance doesn’t exist within the dancer — rather it exists in the relationship between the dancers and the audience. As Briones told the audience, any involvement with the production on our part “keeps the art of dance alive”.

The friendliness and hospitality of this company was clear in the way that connected with the audience after the performance. They hosted a Q&A, and seemed genuinely interested in removing the barrier between artist and audience. To elaborate on the words of Jordan Fife Hunt, they acknowledge that the performance doesn’t exist within the dancer — rather it exists in the relationship between the dancers and the audience. As Briones told the audience, any involvement with the production on our part “keeps the art of dance alive”.

One Response to Benjamin Briones Ballet – Choreographer’s Residency