Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil LeClercq

Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil LeClercq

Written, Directed and Produced by Nancy Buirski

From the opening moments of this film, which include grainy old footage of Tanaquil LeClercq and Jacques D’Amboise performing Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, it’s clear to see what made Tanny so special. Her presence is arresting. At one moment she is majestic, aloof, and almost other worldly. In the next she wears an understated flirtatious expression as her leg turns in and out. In the promenade we see why Robbins referred to her quality of movement as resembling that of an animal. “A young colt soon to become a graceful thoroughbred.” Promenades tend to be so focused and controlled, but in this one LeClercq seems to let go and move with abandon, as if she’s being blown on the wind, placing all trust in D’Amboise to keep her upright.

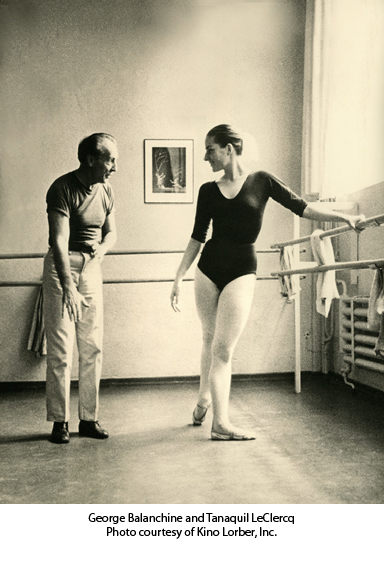

Through a series of wonderful old photos and stories told by George Balanchine’s assistant, Barbara Horgan, and ballerina Patricia McBride, we are drawn into the 1950s incarnation of New York City Ballet and its official studio, The School of American Ballet. Young Tanaquil LeClercq is introduced to us through the eyes of Mr. B, who finds her in the halls of SAB standing alone with her arms crossed after having been kicked out of her class.

Balanchine is described by Ms. Horgan, as always pursuing the next “one”. In some of his most popular pas de deux, we can see a man searching for a woman. Some have speculated that this narrative was autobiographical. For awhile, Tanny was “the one”. Balanchine started out by giving her small roles, eventually going on to choreograph iconic ballets around her.

“Dancers were usually short and quick, stocky and fast,” D’Amboise tells us. But Tanny was tall and elongated, with a strong stage presence. As Balanchine’s muse, she inspired him to take his dances in new directions to suit her movement and her body type.

It is so eerie to learn of the roles that Tanny danced that could have been seen as omens of her coming illness. When she was still a student at SAB, Balanchine was asked to choreograph a ballet for a March of Dimes fund raiser. He created a “grim pas de deux” in which he played the part of polio. Tanny was cast in the role of its victim. In Symphony in C, she famously fell backward into her partner’s arms. Robbins said that he cried when he first saw her do this. In Balanchine’s La Valse, she is dressed in white, then claimed by a figure dressed in black who transforms everything to black, from the stage to her costume, as the company swirls around her.

There is footage from Christmas 1956 of LeClercq and D’Amboise being interviewed for television after having performed the Grand Pas de Deux from The Nutcracker. They spoke about the company’s upcoming tenth anniversary and their winter tour of Europe. It was at this point that the polio vaccine was being administered to the dancers of NYCB — there are even still photos showing the dancers standing in line waiting to receive it. Tanny had been standing in that line, but at the last moment she decided against taking it, fearing it would make her miserable on the flight to Europe.

That decision sealed her fate. On the European tour, without warning, she fell ill and was diagnosed with polio, which paralyzed her legs and one arm.

The film does a great job of depicting what life was like for those in treatment for polio. We are shown footage of hospitals with a row of iron lung machines, into which the ailing are placed. We feel Tanny’s suffering and depression as we hear passages from heartbreaking letters that she exchanged with Robbins after the company returned to New York City, while she and Balanchine stayed behind in Stockholm. The camera shows us her first letter, which looks as if it had been written by a five year old. She could barely hold a pen.

When it became clear that the doctors could not cure her paralysis, Balanchine took it upon himself to attempt to do it. He got involved with prayer groups and spiritual healers. He trained her in Pilates type of exercises. He would even hold her up and place her feet on top of his as he walked, hoping to trick her muscles into remembering how to do it. In the following year, Balanchine choreographed Agon, and Arthur Mitchell points out that in the pas de deux, the man is placing the ballerina into different positions. He felt that this was what Balanchine was doing with Tanny.

It took awhile before she could return to New York City, and it took longer than that before she’d go back to the ballet. Mitchell invited her to teach at Dance Theatre of Harlem. He described her as being able to “zoom” around the studio in her wheel chair in order to give corrections. Virginia Johnson and Lydia Abarca were among her protegees.

In coming to terms with her condition and finding this new role for herself, Tanny was able to say that it’s possible that her polio had been a gift. She went on to coach ballerinas in roles that she had danced. As she found her way, it seems that those around her were able to come to terms with what had happened to her. It’s most impressive that she was able to remain independent after she and Balanchine divorced. Her doctors had told Balanchine that she wouldn’t live to see the age of forty, but she made it almost to eighty.

At the end of the film, D’Amboise deals with a subject that was rarely talked about in public in his generation. Even a full ballet career is short in the context of an entire life. Sooner or later, every dancer has to come to terms with leaving the stage and choosing a new path. For Tanny, it happened way too soon, and in such a cruel fashion. But hers wound up being a great story of resilience and the triumph of the spirit.