Crossroads – Hip Hop and Hoops — An Indigenous Experience

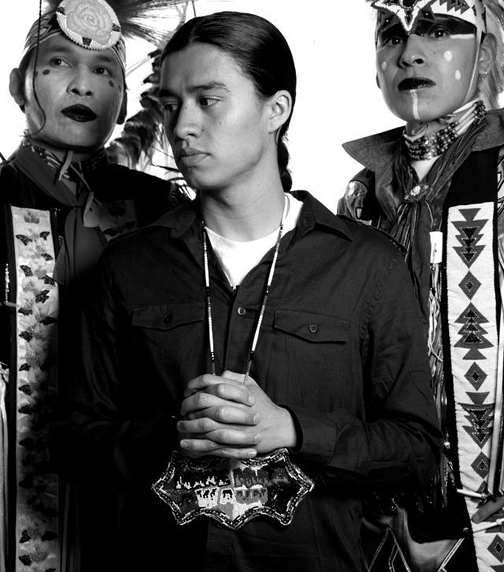

Frank Waln, Samsoche Sampson, Ike Hopper

Chen Dance Center

Friday, November 8, 2013

The Chen Dance Center in New York City’s Chinatown is one of my favorite dance venues. There is a welcoming atmosphere to the place. While young dance students congregate and laugh together in the main hall, guests receive a warm greeting in a reception area. A spread of soft drinks and Chinese appetizers is offered. Artistic Directors H.T. Chen and Dian Dong mill among the guests, engaging them in conversation. This friendly interaction continues during performances in their theater.

H.T. Chen had been attending a conference when he first saw young Lakota hip hop artist Frank Waln performing his original compositions. Waln’s spoken word poems carry the same edge as Eminem’s work, drawing upon personal problems within his family, and the struggles and resilience of his people in the face of colonization. Waln doesn’t pull any punches. It’s a very rare occasion when we in America ever talk about the truth of our history, or about our current relationship with the peoples of the First Nations. But right out of the gate, Waln’s music schools us. His earthy plainspoken songs tell the story of genocide, cultural stereotypes and forced assimilation. He talks about witnessing domestic violence, being abandoned by his father at the age of four, and witnessing the hard work his mother was left to do on her own. Waln said that in younger years he felt very introverted and he couldn’t talk about these things. But through his music, he was able to tell the story. His mission is to bring happiness, health and respect to Indigenous people.

Chen invited Waln to do a residency at the Dance Center. This set up a cross cultural dialogue between the two unique and marginalized communities — that of Native peoples with those who live in Chinatown. The goal was to bring solidarity and awareness to both communities. Before receiving a Gates Millennium Scholarship to attend Columbia College in Chicago, Waln had never left the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. He’d never visited a place like New York City’s Chinatown. Many of the young Chinese students at the Chen Center don’t often leave their Chinatown neighborhood either, and they’d never before met Native people or heard their music or seen them dance. The residency opened communication between the two groups, and resulted in the performance of CrossroadsHip Hop & Hoops – An Indigenous Experience.

The program opened with an original dance and poem performed by a group of Chen Dance Center students, while Samsoche Sampson played the wood flute. As they moved, the children recited a poem they’d created about the American experience of emigration. They named the countries from which their people had come, the type of work that their ancestors had done, and the things that the children do now that they’re here. They mimed to the story and struck poses reminiscent of those seen in Chinese artwork. They ended with the sentiment, “We should all live peacefully.”

Throughout the evening, Waln alternately spoke about his experiences of growing up on the Rosebud Lakota reservation, and then the shock of leaving it to attend college in a big city. Though he spoke candidly about his own personal pain and the struggle of his people, it seemed to always be from a position of strength, from a personal responsibility he felt to talk about the portrayal of Natives in colonized society, no matter how strong the resistance to such conversation within American media and formal education. His words were spoken with great use of rhythm and grooves to the accompaniment of the wood flute, and also to pre-recorded tracks mixing samples of traditional Lakota music.

As Waln sang, Sampson danced with a series of eight hoops. The hoops were rolled on the floor, spun on his arms, and ultimately woven together and around his body in a series of amazing formations. When joined together across his back and along the length of his arms, he looked like a magnificent bird. He laced the hoops together to form what looked like a sacred vessel. All the hoop work is done while Sampson performs a series of two steps or turns on one leg.

Onondaga fancy dancer Ike Hopper joined Sampson, both men dressed in colorful regalia complete with big headpieces, collars and bustles full of ribbons and streamers which flew on the breeze as the men performed turns and Native dances. For the final dance, the Native fancy dancers were joined by a traditional Chinese Lion’s Head dancer and a Taiwanese Diety dancer. It all made for a dazzling spectacle of color and movement across cultures.

Waln’s work is powerful. It is of the utmost importance that his brand of truth telling be heard and seen by those of us who live in big cities like New York City, where there is little to no awareness of the First Peoples who live on this continent. Not only is it crucial that we listen to stories like Waln’s, but it’s every bit as crucial that we hear them told in the voices of those who survived extermination, and those who live by their ways in spite of the effects of colonization. I’m grateful to the Chen Center for presenting this program, as I am to Waln, Sampson and Hopper for their words, music and dance. We need to hear and see more of this type of work.