American Ballet Theatre

Choreography by Alexei Ratmansky

Guggenheim Works & Process

September 30, 2012

In 1986, renowned choreographer Alexei Ratmansky graduated from the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, having never heard the names Rudolf Nureyev or Mikhail Baryshnikov, and having never seen the choreography of George Balanchine. To comply with the policies of the Soviet Union, the Bolshoi did not discuss these men and their works. Ratmansky graduated during a tumultuous era, as the Soviet Union was beginning to collapse, and the VCR and video tape were coming into personal use, introducing him to a whole new world of choreography and dancing.

While being interviewed by former Artistic Director of the Royal Winnepeg Ballet, John Meehan, at Guggenheim’s Works and Process last weekend, Ratmansky described the era as being very disorienting to students who had come up with only strict classical training. Their understanding of choreography mostly revolved around the works of Marius Petipa and Yury Grigorovich. As the outside world began to filter in to Russia, and as Ratmansky left Russia, he originally found himself resisting the new influence, in his mind and his body. This was typical of most dancers who were his contemporaries, trained in the Soviet Union.

Ratmansky danced for Meehan and the Royal Winnepeg Ballet in the early 1990s. Meehan remembered him as being a romantic dancer noted for his very soft landings. A short film showed Ratmansky in performance during that era, and it illustrated the extraordinary quality of his landings. Ratmansky told the audience that this quality came as a result of being made to do petit allegro at an adagio tempo (“It was killing!”) and battement tendu at 32 counts going out and 32 counts coming in.

He said that the Bolshoi always wanted their dancers to “color” the movement. After leaving the Bolshoi, when Ratmansky began to learn new choreography, he was encouraged to just do the steps. “Don’t act. Be more simple.”

He began choreographing for himself, on his own body, then had to learn how to choreograph on other dancers, beginning with his wife Tatiana. One of his first big jobs was a commission from the Kirov to choreograph their Nutcracker. He was on a one month deadline. “Every big work is crazy and intense with very little time.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, people turned their attention away from works of the Soviet era, including The Bright Stream. Fifteen years later, the public began to feel nostalgic for the old works. Ratmansky loved the Shostakovich score and thought that the time could be right to stage a new version of The Bright Stream.

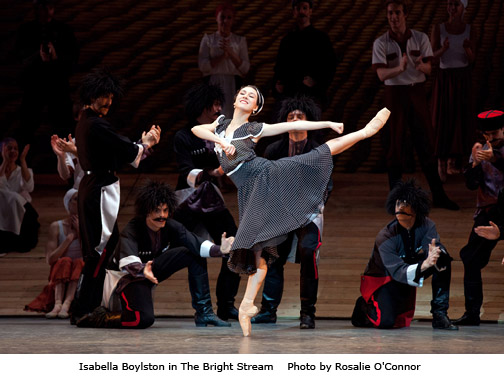

Veronika Part and Stella Abrera danced Zina and the Ballerina, a touching and heartwarming excerpt from Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream, in which two old friends who attended ballet school together are reunited. Every small detail in the movement displays the warmth between the women, especially in the moment when they reach out to lift each other’s chins so that they can see into each other’s eyes.

Even before the premiere of Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream, the Bolshoi Ballet, who did not accept young Ratmansky as a dancer, asked him to take over the entire company. He was 34 at the time. He took up the challenge and found himself in charge of 220 dancers and 20 coaches, some of whom were legends in the ballet world.

At the time that he took over, the Bolshoi was still very conservative, holding dancers in higher esteem than choreographers. So Ratmansky brought in new ballets choreographed by George Balanchine, Twyla Tharp and Christopher Wheeldon among others. In the course of his five year tenure, he introduced thirteen new ballets. There were 250 performances per year on two different stages. He hired new dancers fresh from the school to learn the new repertoire, as the older ones didn’t always “get it”.

Even after five years of working with the Bolshoi, he still felt that the resistance to new works and new choreographers remained very strong in Russia. So he left and came to New York to pursue his choreography. American Ballet Theatre invited him to be their Artist in Residence. He just signed a long term contract with the company, and he enjoys the support he receives and the freedom to create abstract and narrative ballets. He reflected fondly on the company’s history of embracing Russian emigres.

We saw a short excerpt of the scene from the Nutcracker that bridges between the battle scene and the Land of Snow. I’d seen ABT’s new Nutcracker in the middle of a blizzard in 2010, but I’d forgotten how much I’d loved it until I saw this charming section in which Drosselmeyer’s nephew transforms into the Prince. In Ratmansky’s version, two adult dancers enter upstage and mirror some of the movement of the children, who are imagining their future selves. It struck me that in the gestures of the adults, we see traces of the children they once were. As in most Ratmansky ballets, there is always the presence of light hearted humor along with the warmth. I especially loved the excitement of the children as the first snowflakes start to fall.

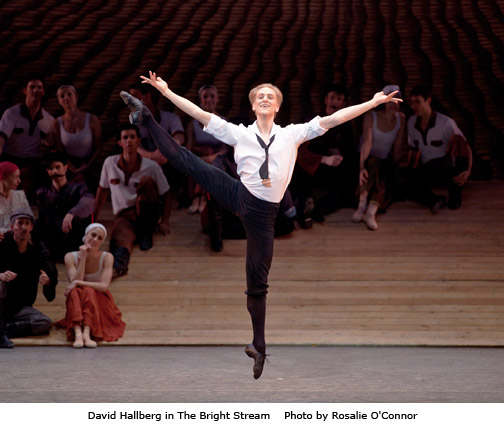

Ballet Mistress Nancy Raffa and principal dancer David Hallberg joined Mr. Meehan to speak of their experiences in working with Ratmansky. Ms. Raffa said that Ratmansky always comes to the studio well prepared with a clear vision and a little black book in which he has worked through the details of his choreography. Mr. Hallberg said that Ratmansky doesn’t move forward until one section is perfected. They will work on eight counts for “what feels like two weeks”. About Ratmansky’s Nutcracker, Mr. Hallberg talked about the nervousness that he and Gillian Murphy experienced the first time that they danced it on stage. “He completely blew what we thought we knew about Nutcracker out of the window.” Hallberg’s words resonated with me and that’s part of the reason why I was so stunned by some of the backlash that the new Nutcracker received. I loved Ratmansky’s telling of the story from the very beginning, precisely because he brought a new and wonderful perspective to it.

Ratmansky’s new ballet, Shostakovich Symphony No. 9 will premiere Thursday, October 18, 2012 at New York City Center.