New York City Ballet

Guggenheim Works & Process

Year of the Rabbit

September 23, 2012

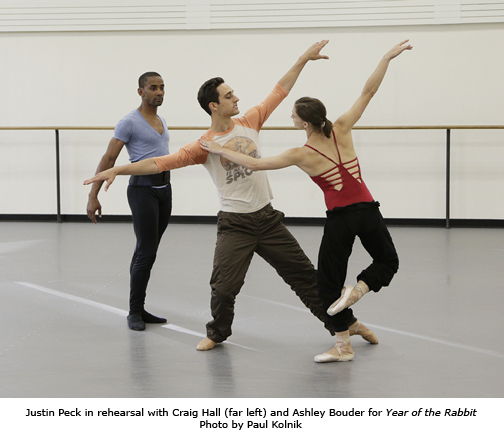

Last weekend as part of the Guggenheim’s Works and Process, New York City Ballet Media Director (and former soloist) Ellen Bar moderated a discussion with NYCB dancer Justin Peck about the new ballet he’s choreographed, Year of the Rabbit, which will be receiving its world premiere on October 5, 2012 at the David H. Koch Theater. Also on the panel were composer Sufjan Stevens and arranger and conductor Michael Atkinson. In addition, the audience was treated to a few excerpts of the ballet, accompanied by a live string quartet.

Year of the Rabbit began as an original work by Sufjan Stevens, composed for electronic instruments with lots of overdubbing. The music describes the signs of the Chinese Zodiac, the characteristics of the animals represented, and their relationships to one another, some in rivalry and some in friendship.

The evening began with a very short film of an excerpt from the ballet being performed on what looked like a Fire Island beach. I was instantly captivated by the swells of the music, which sounded before the movement began. Dense, atmospheric, dramatic, and quirky, it reminded me of the things that excited me most in the progressive rock music of the early 1970s. Later in the evening, as Michael Atkinson described his process in arranging the music for New York City Ballet’s Orchestra, he mentioned the inspiration of composers like Stravinsky and Bartok. Peck first heard Stevens’ music on WNYC-FM and he felt that it would be great for dance. He’d already been commissioned by Peter Martins to create a new ballet when he first approached Stevens about using the music, and having it orchestrated.

Joaquin de Luz seemed perfectly cast for his solo in Year of the Rabbit. Peck explained that rabbits elude their predators by darting back and forth. This is described in the music in quirky phrases of 5/6. As the solo begins, de Luz is shifting his weight from one foot to the other. Once he takes off, he leaves the ground in a spectacular series of leaps and turns, constantly changing direction and constantly traveling until he pauses at the end of the excerpt to look around, as if checking to see if he’s still being hunted.

Teresa Reichlin and Robert Fairchild danced a quieter excerpt. The music slides from rousing to lush, and Ms. Reichlin’s developpes are lyrical, dreamy and expansive. Peck worked to create unconventional movement, guided by the abstract and sometimes weird sounds in the music. The movement is so lovely, with surprising and beautifully unusual details.

It was wonderful to watch Justin Peck coaching Tiler Peck through a short solo that will be danced with a larger cast at the Koch Theatre. He explained that in this section of the choreography, the upper body and lower body moved as two separate parts, with one part initiating the movement for the other. They worked together on little actions which could “stretch out or condense” a passage of music.

Peck mentioned that the full ballet will have a large cast of dancers, and given the density and complexity of the music, I could imagine that a large cast would work superbly and create great excitement on stage.

In the hours when dancers weren’t available to rehearse with him, Peck worked out his ideas on paper. We were shown drawings he’d created, which resembled layered floor plans of the stage, color coded to depict the dancers and the directions in which they’d travel and the spots where they’d arrive. One of the musicians commented, “It looks like a game of Twister.”

I found it interesting that both Stevens and Atkinson had little interest in the ballet before they began working with Peck. Stevens had once been “dragged” to see Apollo, and he had found it to be restrictive, formal and conservative. But as Peck drew him into the ballet world, and took him to see the legendary Balanchine ballets, Stevens came around to understanding them, and then falling in love with them. He said it was “sublime” to see his music expressed with the human body. As a student at Julliard, Atkinson had lived in the same dormitory as SAB students, but admitted that he too needed to be “educated”, and that as his collaboration with Peck continued, so did his appreciation of the classic Balanchine works. It was fascinating to hear the musicians speak about their impressions of the dancers’ process. They remarked about how quickly and how hard the dancers worked and how their communication happened in a language that was different from that of the musicians. Peck explained that part of his job included “translating” between the language of music and the language of dance, saying that dancers hear music differently than musicians. He worked with Atkinson to adjust the dynamics of the music so that the dancers would be able to crucial details when they are on stage in the theater.

I was very excited by what I saw last weekend and I’m so looking forward to seeing the entire ballet.

Year of the Rabbit will have its world premiere on October 5, 2012. Tickets are on sale now.