“What do you mean, he could sing a building?”

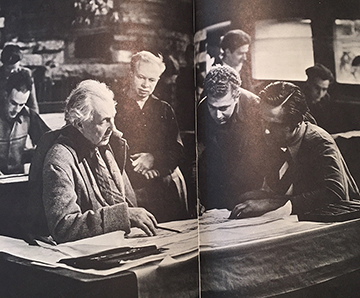

A friend from architecture school was suddenly interested when he found out that I was working as a draftsman for Edgar Tafel, one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s original apprentices at Taliesin.

He’d overheard me describing how much I enjoyed a little office ritual that Edgar practiced a few times each month, when trade magazines arrived in the mail. Back then, circa 1980, these were thick glossy paper magazines packed with colorful photos, interviews, editorials and advertisements. Progressive Architecture. Abitare. Architectural Record. On rare occasions, Architectural Digest would put in an appearance. But the manly men in the office weren’t the target demographic for what they referred to as “Architectural Gourmet”, being that it was a newsstand magazine selling glamour, and not a nuts and bolts trade publication illustrated with wall sections and working drawings.

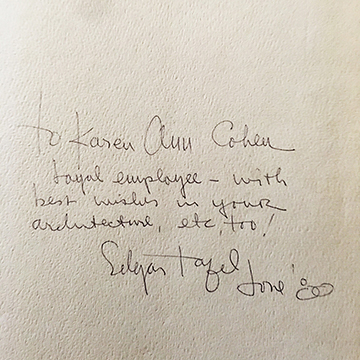

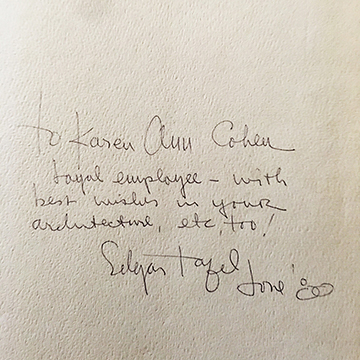

These were the later years of Edgar’s architectural practice. I joined his staff in 1980. He was 68. His first book, Apprentice to Genius, had been published, and he was traveling the world on the lecture circuit, sharing his wonderful stories of Mr. Wright. He’d already closed down his big office and reduced his staff to five of us. Edgar, our interior designer and our bookkeeper occupied the sunny front room of the garden apartment in his gorgeous Greenwich Village townhouse at 14 East 11th Street in New York City.

When a trade magazine was delivered to the office, Edgar would collect it, and visit those of us who worked in the back room – two RAs, Geoff Paine and Al Karman, and me — 22 years old and fresh out of college. I spent my days drafting by hand with a mechanical pencil on mylar. There was a beautiful view outside my window, of the house’s rear garden with its flagstone patio and planters spilling over with ivy.

Edgar would hold court, placing the newly arrived magazine atop a stack of well worn blue line prints, piled on an oversized drawing board opposite the office flat files. He’d invite us to join him as he went, page by page, through the issue.

If a magazine had a photo of a house that piqued his interest, he’d improvise a presentation. His index finger would skate along the roof line, and he’d sing out a note that rose in pitch as it moved up the ridge, growing lower pitched as it skimmed back down to the eaves. He’d roll his tongue to vocalize sounds which mimicked the facade’s texture. If there were articulated joints along the facade, he’d make a sound kind of like a jack hammer, as his finger rapidly drummed against the connections. Or he’d tap his fingertip over a row of windows, singing staccato notes over narrow windows, and longer notes over wide windows. “Baaah – bah – bah – b-b-bah – bah”. It was as if he was reading a rhythm exercise on a staff of sheet music.

The man would look at a photo of a building, and he would sing it. I would later find out that music was central to life at Taliesin, and that Mr. Wright would use musical terms to discuss architecture. I was reminded of this when I read his words about the Martin House in Buffalo, New York. Mr. Wright described it as being a “domestic symphony.”

Edgar’s experience of architecture was such that it could affect every one of his senses. He saw and felt so much beyond the four walls of any room that he visited or designed. I’d certainly never studied with or worked for anyone who appreciated the subject as thoroughly as Edgar did.

He respected an architectural style that took risks

He rarely expressed admiration for the Post Modern fashions of the day. They just weren’t for him, a man who had spent the first ten years of his career at Taliesin, working on Fallingwater, the Johnson Wax Building and a host of private residences designed by Mr. Wright. From his youngest days, he’d sought excitement and change and risk taking in architecture. He’d written gleefully about the early days of the Chicago School, and its architects (Mr. Wright’s master Louis Sullivan among them) whose work and attitudes bucked popular trends and styles so that they could create their own, especially in the form of the high rise building, which was in its infancy then. Edgar lamented that this fell apart circa 1893 when the World’s Columbian Exposition anchored tastes and styles firmly back in Europe and the Beaux Arts for decades to come.

In his own right, he’d so artfully blended Gothic church architecture with Mid-Century Contemporary design in one of my favorite New York City buildings, the Church House of First Presbyterian in Greenwich Village.

He loved a good laugh

During his reviews of the trade pubs, Edgar also had a great eye for catching errors that might have slipped past a magazine’s editor.

One day, he delivered a dramatic reading of an over-the-top letter of complaint excoriating the powers-that-be at the magazine for having published so many egregious errors in a past article on a specific era in architectural history. Its author claimed to be an authority on this era.

Edgar got to the end of the letter and paused for a moment. Then that charismatic smile broke on his face, and there was that devilish gleam of mischief in his eyes. (Mr. Wright had referred to Edgar as being a “bad boy”, and even when he was pushing 70 years old, I could still why.)

He delighted in telling us the name of the person who had authored this letter of complaint.

Ferd Drekfresser.

Which in Yiddish, translates into Horse S*** Eater.

The punchline must have gone right over the heads of the vast majority of the magazine’s readership.

But a punchline could not get past Edgar.

I once heard Edgar Tafel referred to as a bon vivant, and I felt that was the perfect description of him. He seemed to take pleasure and find something humorous or joyous in even the smallest things. He just seemed so entranced with life, and so happy to be alive.

A river of colorful friends continuously came through the office to visit. Edgar kept a packed social calendar, and would often start the business day by joining us in the back room to regale us with reports of where he had been the night before and whom he had seen and what had happened. The stories could grow into staged re-enactments, as happened when he once told us of a dance he attended. While swaying with an imaginary partner, he talked about encountering a rival dancing alongside him. He recounted how they traded barbs and insults throughout the evening without missing a step of the dance.

He so loved a good laugh. One day, out of the blue, he took up a blank sheet of paper. He quickly sketched an elevation of the facade of the simplest, most non-descript one family house. The cartoon was about the size of a couple of postage stamps. Then he proceeded to repeat the sketch, over and over again, with slight alterations each time, claiming that these were “homages” to the work of the greats, as he imagined the way that each popular architect would visualize it. Mr. Wright’s would have a cantilevered roof. Corbu’s would be up on pilotis – reinforced concrete stilts. Phillip Johnson’s had the little Chippendale cut out at the top, in honor of his AT&T Building which was under construction at the time. Mies’ would be a glass and steel grid. Paul Rudolph’s had towers on its corners, bearing resemblance to the Yale Art and Architecture Building. Luis Barrigan’s was a stark concrete form, a stair without a railing, and a horse posed in front of it. This paper was passed around the office for months, as each one of us, and every visiting colleague of Edgar’s, was invited to add another cartoon or an embellishment to the collection. It grew to three pages and Edgar delighted in presenting it to visitors at the office.

Another wonderful collection in the office was his George Washington memorabilia, which covered the walls of a short corridor outside the office bathroom. His friends, colleagues and clients got into the spirit of the collection, and always brought him new pieces to add. There were postcards, art prints, banners. Nothing was too kitsch to take its place in the makeshift gallery. Edgar knew how to curate and present it as if it was high art.

The architect’s home

While trying to recall all the details of Edgar’s apartment on the parlor floor, I couldn’t be quite sure if I’d got it right. I could remember the open Wright-ian floor plan, the beautiful grand piano and the profusion of Japanese prints. Other than that, my memories are hazy – I wasn’t up there very often. So I took my chances and ran a search to see if any interior shots had ever been posted. I came across a lucky find – a feature in the September 1954 issue of House Beautiful, showing detailed photos of Edgar’s design.

When I first arrived in 1980, the parlor floor still looked nearly the same as it does in the House Beautiful spread. On the bottom of the second page, there is a photo of the back room on the garden floor. When it was transformed into Edgar’s office, that’s where I worked.

Edgar did not share Mr. Wright’s dislike of paint. Though he did leave an exposed brick wall inside the apartment, the building’s brick facade was painted a powerful pine green, which looked fantastic with the black window frames, and the polished brass plaque near the door which bore the words “Edgar Tafel, Architect”. Sadly, a visit to Google Maps Street View confirms that the facade of 14 East 11th Street was steam cleaned and that its interior was just about gutted and rebuilt.

The example he set

Edgar’s leadership created such a wonderful and warm feeling of camaraderie among the employees. In the five years that I worked in his office, I only ever heard him raise his voice once or twice, and it was always to someone on the phone, never to one of us employees or to the contractors. My superiors were so incredibly kind to me, much more so than at any other office I’d every worked in, architectural or otherwise.

Being that I worked for Edgar in the early 1980s, like every artistic kid, I played in a new wave/punk band after hours. Whenever Edgar saw my guitar around the office, he always referred to it as my machine gun or a banjo. I was so touched when he actually came down to s.n.a.f.u., a club in Chelsea, to see me perform very noisy music with a very noisy band. It was a Tuesday night, the place was empty and we went on so late, but there was Edgar, with one of the female clients as his guest, and he was going to have a fine time whether our guitars were out of tune or not.

I remember Al Karman as being endlessly patient with me, as well as being an unending source of brilliant one liners. He was so quick. A day didn’t go by without him making me laugh. He knew the names of the receptionists and administrative staff at every contractor’s office and always took the time to chat with them. While putting together construction documents, going through Sweets Catalog and making endless phone calls to manufacturers, he’d never get directly to the business at hand when his call was answered. He always humanized the exchange, asking what part of the country he’d just called, and what the weather was like. It was such a pleasure to work with him. Al left to open his own office about a year or so after I met him.

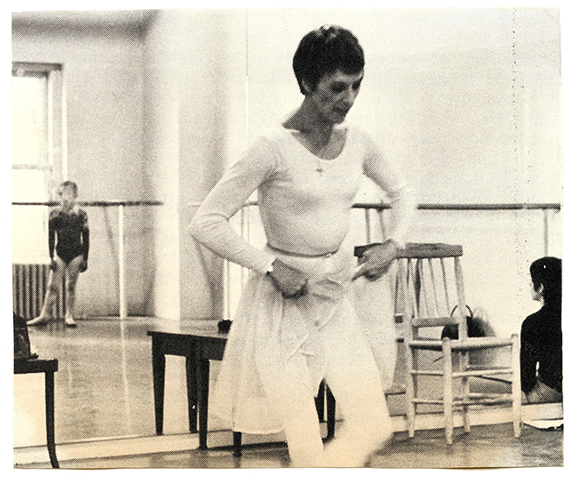

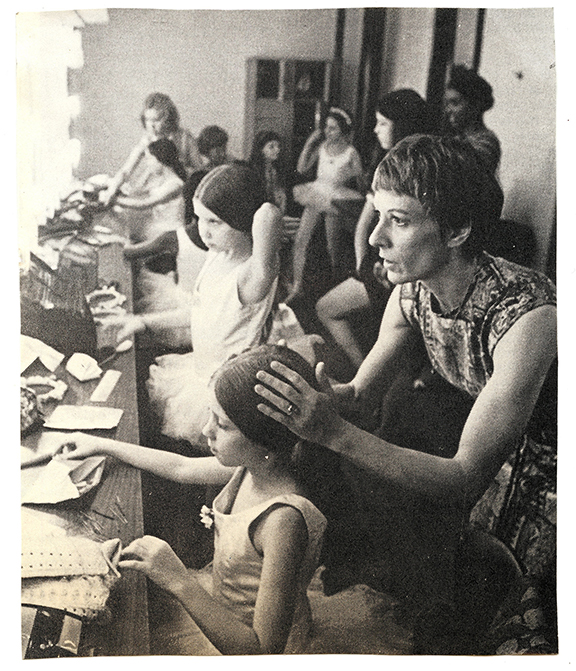

So I spent the bulk of my time taking instruction from Geoff Paine. Geoff was reserved, with an incredibly sharp eye. He was referred to as the office “nit picker”, which was great for me, because his corrections really helped me up my game. To this day, it’s his standard that I always try to match, and his voice that I still hear in my head, holding me to that standard. We also shared a great love for the ballet, and it was fun to gossip with him about the goings on at the big companies based in New York City. Long after I left Edgar’s office, Geoff and I kept in touch with the yearly exchange of Christmas cards. His cards always included an ample personal note, hand written in his impeccable architect’s lettering.

Edgar also designed and sent out Christmas cards. In the 1980s, they were always printed in Cherokee Red ink on beautiful ivory stock. You can see the design of an earlier card here.

I was so damn young when I worked for Edgar. I just cringe when I think back on some of the naive things I said and stupid mistakes I made in those days, at the very beginning or my architecture career. But then I don’t feel so bad about it, remembering that Edgar once told me about a certain building he’d worked on early in his own career, and how he was willing to walk a quarter mile out of his way to avoid seeing it and being faced with his own rookie mistakes.

Long after I left Edgar’s office, I received sporadic phone calls from him. They always came when he’d heard a new joke with a punchline that could only be appreciated by someone whose parents spoke Yiddish. I was always so happy to hear from him.

Even though he lived to be 99 years old, I was saddened when a Google alert announced his death in January 2011. A few years later, Geoff Paine passed. I was surprised by how bereft I felt. The five years that I spent in that office left such an enormous impression upon me, and I still think of Edgar and Geoff all these years later, and how wonderful it was to have been a young draftsman working for them.

~~~~~

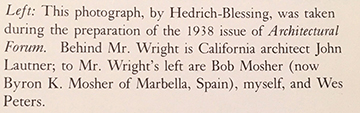

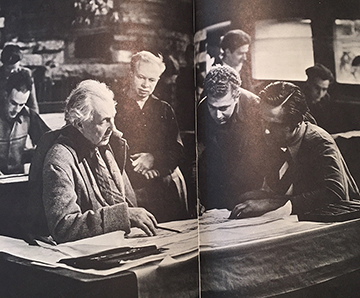

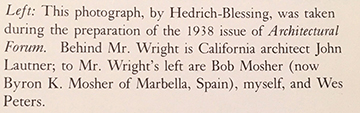

All images in this post are photos from the pages of Apprentice to Genius by Edgar Tafel, Architect

Premiere Division

Premiere Division