Just enough to make the street look pretty

Not enough to make much trouble

Anna Sokolow’s Lyric Suite

Sokolow Theatre Dance Ensemble

presents

Sounds of Sokolow

Lyric Suite

The Theatre at the 14th Street Y

December 8, 2012

All photos by Meems

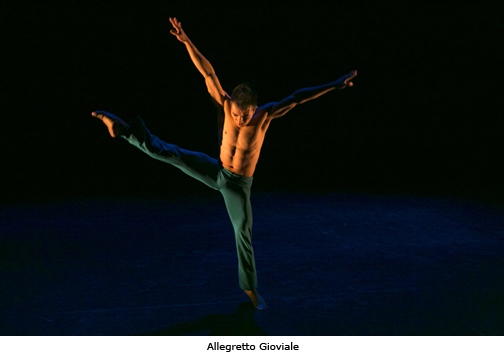

In the opening passage of Lyric Suite, Allegretto Gioviale, dancer Richard Scandola stands alone and shirtless. He looks around, guarding his own back, and he seems careful not to make a sound, as if he is hunting. Slowly and deliberately, he shifts his weight. The passage opens up only slightly as he moves forward in a series of turns until, like several of the passages of Lyric Suite, it closes with the same movement with which it opened. This passage was dedicated by Anna Sokolow to Vaslav Nijinsky, and even though the music and dance are non-narrative, the theatricality is always there. The dance does not respond literally to composer Alban Berg’s atonal music, but rather it works with the music to conjure emotion and atmospheres.

Francesca Todesco dances Andante Amoroso. There is interesting movement with the hands, fingers woven together as if to make a basket which she holds close to her heart. They move behind her neck, pulling on her head before she extends her arms overhead, hands turned palms up. It made me feel as if she was searching or beckoning to the heavens while reconciling the pull of earth. In another sequence, she seems to be rocking on the waves of the ocean before her gaze returns upward. There is a long and dramatic series of turns in which her head sometimes drops. In the closing moments, she is reaching skyward as her body sinks and finally falls to the floor.

Allegro Misterioso follows, danced by Samantha Geracht. She enters in a floor length gray skirt. Her hands tremble as she lifts them. She seems even further bound to the earth, sinking, falling, and getting back up. She runs frantically around the stage, at times moving backwards till the end of the passage, where she seems resigned to her fate, stuck on the floor and unable to rise as the stage goes black.

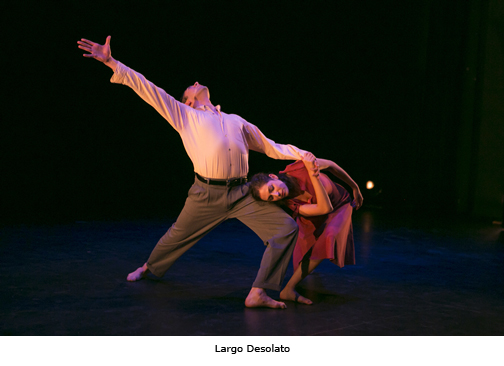

Melissa Sobel and Gregory Youdan danced Largo Desolato. The partnering is beautiful and the movement in this section is more lyrical and slow, but with intensity. It reminded me of Anna Sokolow’s quote, “True lyricism has to have passion and strength underneath it. For an arm to come up beautifully and with meaning, it has to have great power and energy.” There was a lovely and unusual sequence as the dancers sit on the floor and advance toward each other with a high developpe initiating each movement. They stand and grasp each other by the forearms, backs arched backward and chests lifted as if in euphoria. Simple movements like ronde de jambs and tendus on the floor are used to lovely effect. The gentle beauty of this passage seems to resolve the tension set up in the Allegro Misterioso.

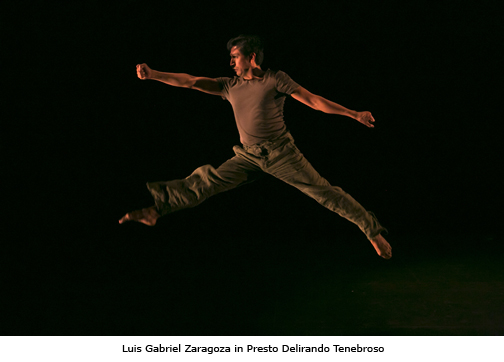

But the tension returns, builds and explodes with a bravura performance by Luis Gabriel Zaragoza in Presto Delirando Tenebroso. Zaragoza’s dancing is riveting and dramatic — I found it impossible to take my eyes off of him even for a moment. His facial expressions are haunting and heart breaking. He dances the role of one who’s been captured and dehumanized, like a soldier or a prisoner, but the humanity within him struggles to be set free. There are dramatic changes in direction that pivot rapidly and unexpectedly. He executes a series of grand jetes but he slowly loses steam, as if the life is being drained from him. He struggles to open up but winds up falling.

Lyric Suite closes with a quartet, Adagio Appassionato. Four women dressed in floor length red skirts travel along the stage mostly at close quarters. The choreography plays with level changes and the rippling swirling of the skirts to great effect. Some of the patterns seem to be more formal — the women stand in a square at one point, as if for a reel. Toward the end there is another interesting sequence in which the dancers seem to be moving away from one another, yet the group remains at close quarters.

Anna Sokolow’s work was pivotal in the world of modern dance. It was wonderful to see it performed by Sokolow Theatre Dance Ensemble and it would be great to see more modern companies tackle her repertoire.

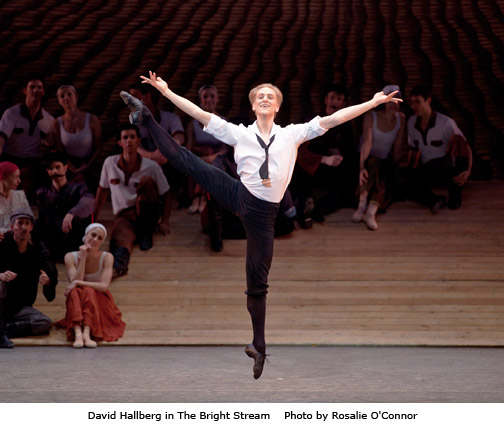

Choreography by Ratmansky

American Ballet Theatre

Choreography by Alexei Ratmansky

Guggenheim Works & Process

September 30, 2012

In 1986, renowned choreographer Alexei Ratmansky graduated from the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, having never heard the names Rudolf Nureyev or Mikhail Baryshnikov, and having never seen the choreography of George Balanchine. To comply with the policies of the Soviet Union, the Bolshoi did not discuss these men and their works. Ratmansky graduated during a tumultuous era, as the Soviet Union was beginning to collapse, and the VCR and video tape were coming into personal use, introducing him to a whole new world of choreography and dancing.

While being interviewed by former Artistic Director of the Royal Winnepeg Ballet, John Meehan, at Guggenheim’s Works and Process last weekend, Ratmansky described the era as being very disorienting to students who had come up with only strict classical training. Their understanding of choreography mostly revolved around the works of Marius Petipa and Yury Grigorovich. As the outside world began to filter in to Russia, and as Ratmansky left Russia, he originally found himself resisting the new influence, in his mind and his body. This was typical of most dancers who were his contemporaries, trained in the Soviet Union.

Ratmansky danced for Meehan and the Royal Winnepeg Ballet in the early 1990s. Meehan remembered him as being a romantic dancer noted for his very soft landings. A short film showed Ratmansky in performance during that era, and it illustrated the extraordinary quality of his landings. Ratmansky told the audience that this quality came as a result of being made to do petit allegro at an adagio tempo (“It was killing!”) and battement tendu at 32 counts going out and 32 counts coming in.

He said that the Bolshoi always wanted their dancers to “color” the movement. After leaving the Bolshoi, when Ratmansky began to learn new choreography, he was encouraged to just do the steps. “Don’t act. Be more simple.”

He began choreographing for himself, on his own body, then had to learn how to choreograph on other dancers, beginning with his wife Tatiana. One of his first big jobs was a commission from the Kirov to choreograph their Nutcracker. He was on a one month deadline. “Every big work is crazy and intense with very little time.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, people turned their attention away from works of the Soviet era, including The Bright Stream. Fifteen years later, the public began to feel nostalgic for the old works. Ratmansky loved the Shostakovich score and thought that the time could be right to stage a new version of The Bright Stream.

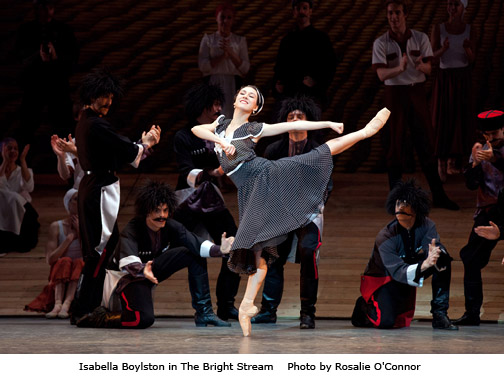

Veronika Part and Stella Abrera danced Zina and the Ballerina, a touching and heartwarming excerpt from Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream, in which two old friends who attended ballet school together are reunited. Every small detail in the movement displays the warmth between the women, especially in the moment when they reach out to lift each other’s chins so that they can see into each other’s eyes.

Even before the premiere of Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream, the Bolshoi Ballet, who did not accept young Ratmansky as a dancer, asked him to take over the entire company. He was 34 at the time. He took up the challenge and found himself in charge of 220 dancers and 20 coaches, some of whom were legends in the ballet world.

At the time that he took over, the Bolshoi was still very conservative, holding dancers in higher esteem than choreographers. So Ratmansky brought in new ballets choreographed by George Balanchine, Twyla Tharp and Christopher Wheeldon among others. In the course of his five year tenure, he introduced thirteen new ballets. There were 250 performances per year on two different stages. He hired new dancers fresh from the school to learn the new repertoire, as the older ones didn’t always “get it”.

Even after five years of working with the Bolshoi, he still felt that the resistance to new works and new choreographers remained very strong in Russia. So he left and came to New York to pursue his choreography. American Ballet Theatre invited him to be their Artist in Residence. He just signed a long term contract with the company, and he enjoys the support he receives and the freedom to create abstract and narrative ballets. He reflected fondly on the company’s history of embracing Russian emigres.

We saw a short excerpt of the scene from the Nutcracker that bridges between the battle scene and the Land of Snow. I’d seen ABT’s new Nutcracker in the middle of a blizzard in 2010, but I’d forgotten how much I’d loved it until I saw this charming section in which Drosselmeyer’s nephew transforms into the Prince. In Ratmansky’s version, two adult dancers enter upstage and mirror some of the movement of the children, who are imagining their future selves. It struck me that in the gestures of the adults, we see traces of the children they once were. As in most Ratmansky ballets, there is always the presence of light hearted humor along with the warmth. I especially loved the excitement of the children as the first snowflakes start to fall.

Ballet Mistress Nancy Raffa and principal dancer David Hallberg joined Mr. Meehan to speak of their experiences in working with Ratmansky. Ms. Raffa said that Ratmansky always comes to the studio well prepared with a clear vision and a little black book in which he has worked through the details of his choreography. Mr. Hallberg said that Ratmansky doesn’t move forward until one section is perfected. They will work on eight counts for “what feels like two weeks”. About Ratmansky’s Nutcracker, Mr. Hallberg talked about the nervousness that he and Gillian Murphy experienced the first time that they danced it on stage. “He completely blew what we thought we knew about Nutcracker out of the window.” Hallberg’s words resonated with me and that’s part of the reason why I was so stunned by some of the backlash that the new Nutcracker received. I loved Ratmansky’s telling of the story from the very beginning, precisely because he brought a new and wonderful perspective to it.

Ratmansky’s new ballet, Shostakovich Symphony No. 9 will premiere Thursday, October 18, 2012 at New York City Center.

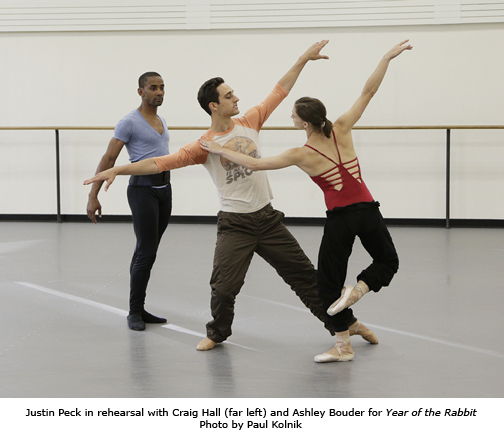

New York City Ballet – Guggenheim Works & Process – Year of the Rabbit

New York City Ballet

Guggenheim Works & Process

Year of the Rabbit

September 23, 2012

Last weekend as part of the Guggenheim’s Works and Process, New York City Ballet Media Director (and former soloist) Ellen Bar moderated a discussion with NYCB dancer Justin Peck about the new ballet he’s choreographed, Year of the Rabbit, which will be receiving its world premiere on October 5, 2012 at the David H. Koch Theater. Also on the panel were composer Sufjan Stevens and arranger and conductor Michael Atkinson. In addition, the audience was treated to a few excerpts of the ballet, accompanied by a live string quartet.

Year of the Rabbit began as an original work by Sufjan Stevens, composed for electronic instruments with lots of overdubbing. The music describes the signs of the Chinese Zodiac, the characteristics of the animals represented, and their relationships to one another, some in rivalry and some in friendship.

The evening began with a very short film of an excerpt from the ballet being performed on what looked like a Fire Island beach. I was instantly captivated by the swells of the music, which sounded before the movement began. Dense, atmospheric, dramatic, and quirky, it reminded me of the things that excited me most in the progressive rock music of the early 1970s. Later in the evening, as Michael Atkinson described his process in arranging the music for New York City Ballet’s Orchestra, he mentioned the inspiration of composers like Stravinsky and Bartok. Peck first heard Stevens’ music on WNYC-FM and he felt that it would be great for dance. He’d already been commissioned by Peter Martins to create a new ballet when he first approached Stevens about using the music, and having it orchestrated.

Joaquin de Luz seemed perfectly cast for his solo in Year of the Rabbit. Peck explained that rabbits elude their predators by darting back and forth. This is described in the music in quirky phrases of 5/6. As the solo begins, de Luz is shifting his weight from one foot to the other. Once he takes off, he leaves the ground in a spectacular series of leaps and turns, constantly changing direction and constantly traveling until he pauses at the end of the excerpt to look around, as if checking to see if he’s still being hunted.

Teresa Reichlin and Robert Fairchild danced a quieter excerpt. The music slides from rousing to lush, and Ms. Reichlin’s developpes are lyrical, dreamy and expansive. Peck worked to create unconventional movement, guided by the abstract and sometimes weird sounds in the music. The movement is so lovely, with surprising and beautifully unusual details.

It was wonderful to watch Justin Peck coaching Tiler Peck through a short solo that will be danced with a larger cast at the Koch Theatre. He explained that in this section of the choreography, the upper body and lower body moved as two separate parts, with one part initiating the movement for the other. They worked together on little actions which could “stretch out or condense” a passage of music.

Peck mentioned that the full ballet will have a large cast of dancers, and given the density and complexity of the music, I could imagine that a large cast would work superbly and create great excitement on stage.

In the hours when dancers weren’t available to rehearse with him, Peck worked out his ideas on paper. We were shown drawings he’d created, which resembled layered floor plans of the stage, color coded to depict the dancers and the directions in which they’d travel and the spots where they’d arrive. One of the musicians commented, “It looks like a game of Twister.”

I found it interesting that both Stevens and Atkinson had little interest in the ballet before they began working with Peck. Stevens had once been “dragged” to see Apollo, and he had found it to be restrictive, formal and conservative. But as Peck drew him into the ballet world, and took him to see the legendary Balanchine ballets, Stevens came around to understanding them, and then falling in love with them. He said it was “sublime” to see his music expressed with the human body. As a student at Julliard, Atkinson had lived in the same dormitory as SAB students, but admitted that he too needed to be “educated”, and that as his collaboration with Peck continued, so did his appreciation of the classic Balanchine works. It was fascinating to hear the musicians speak about their impressions of the dancers’ process. They remarked about how quickly and how hard the dancers worked and how their communication happened in a language that was different from that of the musicians. Peck explained that part of his job included “translating” between the language of music and the language of dance, saying that dancers hear music differently than musicians. He worked with Atkinson to adjust the dynamics of the music so that the dancers would be able to crucial details when they are on stage in the theater.

I was very excited by what I saw last weekend and I’m so looking forward to seeing the entire ballet.

Year of the Rabbit will have its world premiere on October 5, 2012. Tickets are on sale now.

Pacific Northwest Ballet – New York Season Preview

Pacific Northwest Ballet – New York Season Preview

Works and Process at The Guggenheim

Sunday, September 8, 2012

This lecture and performance given by Artistic Director Peter Boal and Pacific Northwest Ballet dealt with the endlessly fascinating topic of Balanchine’s choreography. I have found that no matter how long I spend in the theater seeing Balanchine’s works and reading about them, there’s always something new to learn, which so enhances my appreciation of the work. Mr. Boal along with the gorgeous dancers of PNB, Maria Chapman, Carla Körbes, Seth Orza, Lesley Rausch, Benjamin Griffiths, and Matthew Renko, explored the topic of changes made throughout the lives of the Balanchine ballets. Ballets discussed included Apollo, Four Temperaments and Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux.

There have been a host of different reasons for the changes made to the ballets. Mr. Boal told us that in the case of Apollo, “the boss” (Diaghilev) told Mr. B (who was 24 years old when the ballet received its world premiere) to make the changes. At other times, choreography was adjusted to suit different stages and different casts. Mr. Boal, who ironically was awarded his first contract with New York City Ballet on the day Mr. B passed away, learned the choreography from Peter Martins, Jerome Robbins, Suzanne Farrell and others from NYCB. When he went on to learn the same roles with other companies, including PNB, he found their choreography to be different from NYCB’s version, and different from one company to the next.

I have only ever seen New York City Ballet’s production of Apollo performed live, with its unadorned costumes and bare stage, so I found it really interesting to see still photos from the Ballet Russes production which included ornate costumes (the first round chosen by Diaghilev and a later version created by Coco Chanel) and a set incorporating Mount Parnassas. Quite a contrast. Mr. Boal also showed film clips of Jacques d’Amboise dancing the role in 1960, and Mikhail Baryshnikov performing it in 1978.

Even as a very young choreographer, Balanchine made the deliberate decision to remove entire passages of the story of Apollo and he was bold in answering his critics when they challenged him on that score. “I can do with my ballets whatever I want.” He understood the power that existed in editing one’s work.

It was wonderful to have Mr. Boal draw our attention to details in the choreography that helped to tell the story. After Seth Orza danced the first solo with lovely and quiet control, Mr. Boal described the movement in such beautiful language, saying that the dancer was to move like a “newborn colt”. A series of piques which melt in plie symbolize the way a newborn’s legs might fail beneath the weight of his body as he first figures out how to walk.

Carla Körbes’ Terpsichore left me swooning — she is just stunning. Mr. Boal pointed out that in her manege, her saute arabesques lead with the chest, rather than with the arm. This one subtle little difference made her appear as if she was floating above the ground. As Mr. Orza and Ms. Körbes danced together, Mr. Boal pointed out that Terpsichore doesn’t “engage Apollo with the eyes”, but rather with the hands. It’s such a small detail, and so crucial to the story being told by the movement.

Ben Griffiths performed a more current version of Melancholic from Four Temperaments, with heaviness in his shoulders and softer lines while Matthew Renko danced an older version which was sharper and more forceful. Mr. Boal pointed out that in the current version, the stage is empty when the music starts, and that can build tension before the dancer even steps on stage. The audience becomes concerned that the character is late, or that the dancer may have missed his cue. In the earlier version, Apollo is on stage when the music starts.

Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux has had the most revisions. Designed with the intention of being a “showstopper” Balanchine and other choreographers constantly adjusted it to showcase the different strengths of the different dancers who performed the piece. A series of fabulous film clips were shown, alternating D’Amboise’s performance with Baryshnikov’s, illustrating the differences in choreography for each dancer.

PNB closed out the evening in spectacular style, performing an excerpt from the ballet. Though the stage was too small, and there was a wobble here and there, they delivered the most rousing performance that made me want to jump to my feet. This is a wonderful company that we in New York City just don’t see enough of. Their lines are so pure and their movement is so fluid. But beyond that, the dancers possess great charisma. Their dancing was playful, and they seemed to be enjoying themselves so much that the audience could not remain unaffected.

In addition to performing at Fall for Dance in October, Pacific Northwest Ballet will return to City Center to perform an All Balanchine Program and Jean-Christophe Maillot’s Roméo et Juliette in February 2013. Tickets are on sale now.

Sunday in Sunset Park

Spent Sunday afternoon cruising around Sunset Park attending Open Studio Weekend.

I love the intimacy of Open Studios. It’s so cool to see art work in process, on the easel, and to see the tools the artists choose and the images that cover their pin up spaces. Most of the artists were very warm and welcoming, chatty and generous.

This was my first visit to Chashama, a big open space in the old Brooklyn Army Terminal which is full of artists’ studios. The photos show the view from the Army Terminal. It was such a clear beautiful day and the puffy clouds in the blue sky were just breathtaking.

Latin Choreographer’s Festival 2012

Latin Choreographer’s Festival

Dance New Amsterdam

Sunday, July 15, 2012 – Program A

All Photos by Rachel Neville

Every year at this time I open a new file and begin typing up superlatives about the Latin Choreographer’s Festival. This year is no different. Once again, the festival brought a diverse program featuring numerous Latin voices in choreography, and an array of beautiful dancers to present the work.

The festival, dedicated to the memory of Jose Limon, opened with a short black and white film made in Mexico about Limon’s life and work. It covered the ways in which Limon’s masculine choreography “electrified the world”. Included was a short discussion of the ways in which Limon was challenged to assimilate in America. Variations on this theme showed up again in some of the other dances presented at the festival.

Another theme that ran through some of the pieces was the depiction of the stresses of everyday life, and the search for a way in which to move beyond them. Zachary Tracz danced Carolina Rivera’s Bodhi with great style and expression. His torso contracts and his arms are thrown forward, as if he’s negotiating some kind of rough terrain, and moving forward under adverse conditions. His hands tremble as he looks toward the heavens. Then his body tenses and his hands close into fists. The tension builds until he finds himself pressed against the floor, where he finds a very small gong. Once the gong is rung, the transformation into serenity begins.

Katia Garza and Sebastian Serra deliver emotion packed performances in the ballet Ojala, choreographed by Ana Cuellar. There is trouble between their two characters and based on the lovely words printed in the program, they’ve either chosen to go their separate ways, or they’ve been separated by death. Garza’s movement is marked with longing and searching. They embrace, and then with sad faces, they drift apart. The choreography is punctuated with beautiful lifts and great use of counterpoint.

Katia Garza and Sebastian Serra deliver emotion packed performances in the ballet Ojala, choreographed by Ana Cuellar. There is trouble between their two characters and based on the lovely words printed in the program, they’ve either chosen to go their separate ways, or they’ve been separated by death. Garza’s movement is marked with longing and searching. They embrace, and then with sad faces, they drift apart. The choreography is punctuated with beautiful lifts and great use of counterpoint.

Maribel Michel danced an excerpt called Paranoia from a longer piece choreographed by Miguel Angel Palmeros, titled Retratos de Locura (Portraits of Madness), an intense modern piece with excellent expressive dancing by Michel. In the harsh lighting, at times she seems possessed by fear or pain — and at other times she seems to be in prayer, but she moves forward nonetheless. Her eyes are wide, her brow furrowed, her movement defensive. She stays low to the ground and the industrial sounding music beeps as tension builds. From time to time, vignettes are played out along the back wall of the stage, by a couple dressed in gray. They carry out an animated argument until they go static, their fingers still waggling.

I felt a real soft spot for Eloy Barragan’s Tree. This piece addressed life in the diaspora, where the houses don’t ever quite feel like home, and the landscape is constantly changing. Dancer Steven Gray displayed quiet strength, great musicality and seamless transitions between fast and slower motion. I liked the originality of this piece and its beautiful rolling movement which continuously unfolded and never seemed to stop, accompanying a yearning piece of violin music by Max Richter.

Ursula Verduzco’s Hidden Souls, which illustrates the domination and silencing of women, has atmospheres that are at times eerie and almost medieval. A single woman moves along a diagonal in a ritualistic fashion to choral music by Dead Can Dance. She is clad in black and her head and mouth are covered. She struggles to get the attention, or even the mercy of an angry and domineering man who refuses to listen to her. A small group of dancers, each dragging a chair, pick ups on the canon of movement while the main character seems to have found her own power. The music changes and she begins to move with authority. I especially liked this passage in the piece, and the effective use of the chairs to create changes in height and level. The counterpoint is beautiful and haunting. It seemed to tell the story of the resilience of the human spirit, and it’s determination to keep fighting, even if the battle is already lost. Then, to tell the sad story of the fate of these women, they wind up moving in unison with their overlord. This is a very dramatic and gripping piece.

Ursula Verduzco’s Hidden Souls, which illustrates the domination and silencing of women, has atmospheres that are at times eerie and almost medieval. A single woman moves along a diagonal in a ritualistic fashion to choral music by Dead Can Dance. She is clad in black and her head and mouth are covered. She struggles to get the attention, or even the mercy of an angry and domineering man who refuses to listen to her. A small group of dancers, each dragging a chair, pick ups on the canon of movement while the main character seems to have found her own power. The music changes and she begins to move with authority. I especially liked this passage in the piece, and the effective use of the chairs to create changes in height and level. The counterpoint is beautiful and haunting. It seemed to tell the story of the resilience of the human spirit, and it’s determination to keep fighting, even if the battle is already lost. Then, to tell the sad story of the fate of these women, they wind up moving in unison with their overlord. This is a very dramatic and gripping piece.

Benjamin Briones’ Al Reves, explores the drama of conflicting feelings in a relationship. Ursula Verduzco and Steven Gray swagger along the edges of the spotlight, eyeing each other like boxers in a ring might do right before the match. Their movement is confrontational, each one lifting their chest and chin. They embrace, they push each other away, they chatter at each other so that neither can hear what the other is saying, and despite all this, the tenderness between them keeps rolling up to the surface. Sometimes much is said in the absence of a movement – Verduzco falls to the floor and Gray offers her a hand up, but she remains still — reluctant to accept his kind gesture.

Choreographer and dancer Felix Cruz gave a compelling and emotional performance of Other Side of Someday, giving voice to life’s frustrations and the wish to navigate past stormy seas into calmer waters. Cruz stands stoically even as he is being attacked. His hair is pulled and he’s slammed to the floor, but he recovers and maintains an impassive stare. When he is finally punched in the face, he takes on the role of the attacker and turns the violence on himself. He slaps himself. The soundtrack becomes menacing as he flails about, falling very heavily again and again, his body tense and stricken. He recovers as the strains of Judy Garland’s Over the Rainbow play, and he lip synchs the lyrics with surprising emotion, sensitivity and yearning. This was a very touching performance.

Ferdinand DeJesus’ Bitter Earth was danced by Asha Davis to the Dinah Washington classic about the sorrows of love and loss. She is dressed in white and despite the blues atmosphere created by the music, she appears to be rising up and moving ahead in hope. The movement was at times reminiscent of Ailey’s early work, and Davis delivered a genuine and unpretentious performance.

Manuel Vignouelle’s edgy and ambitious In A Box was one of the festival’s highlights. It dealt with matters that have been weighing heavily on me recently – specifically how compartmentalized and “boxed in” we can become in a place like New York City. Parent wears an arresting expression of innocence and searching — there is an originality to her dancing that I just adored. As the dance opens, her movement is very confined – she pushes at the invisible walls which have her trapped and she does not travel. It’s only when Vignouelle joins her that the movement becomes a bit more expansive. They may shake and vibrate, but the energy is then released. There were some interesting and original canons in this piece, along with a few towering lifts which were resolved with dramatic falls. Vignouelle took risks with this piece and they paid off.

Manuel Vignouelle’s edgy and ambitious In A Box was one of the festival’s highlights. It dealt with matters that have been weighing heavily on me recently – specifically how compartmentalized and “boxed in” we can become in a place like New York City. Parent wears an arresting expression of innocence and searching — there is an originality to her dancing that I just adored. As the dance opens, her movement is very confined – she pushes at the invisible walls which have her trapped and she does not travel. It’s only when Vignouelle joins her that the movement becomes a bit more expansive. They may shake and vibrate, but the energy is then released. There were some interesting and original canons in this piece, along with a few towering lifts which were resolved with dramatic falls. Vignouelle took risks with this piece and they paid off.

The evening closed with David Fernandez’s Beethoven Sonatas, a playful ballet piece full of good humor. At times the body directly mimics the music – small fast movement of the feet will echo a trill on the piano. A dancer’s hands will fall on an imaginary piano keyboard, miming as if they were playing the closing chord of the music. The dancers tug on the lapels of their tux jackets, or wag their fingers while doing neck isolations as if to say, “Oh no you didn’t.” It was a very sweet piece, danced beautifully by Dorrie Garland, Karina Teran, Laura DiOrio and Roberto Lara

Summer Begins

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about ancestors. The spirits of the ancestors of the Canarsee and Nyack who live in this part of the world. But also of my own ancestors, whose blood continues to course through my veins. I know so little about them, yet they remain such a huge presence in my life.

They lived in the diaspora for millennia. I can’t even be sure where they were or how they lived. I’ve only got some sketchy information about my grandparents, and one great grand parent.

I have a feeling that they must have spent many generations in northeast Europe. I think that would explain my love of cold climates and winter landscapes. I tend to wilt in summer.

So I seek out the quietest, most overgrown spot in the backyard, which is lush and green and full of life. I listen to what it has to tell me.

Even at my advanced age and after so many years of living here, there are still moments that leave me amazed. Like the ones in which I see the beginnings of an eggplant growing where there was only a flower a couple of days earlier.

What is the summer landscape telling you?

This fig bush was planted by the previous owners of this house, who babied it and wrapped it in burlap in the winter. We’ve been living here for 26 years and we’ve done little to care for it. But it just keeps growing and bearing fruit. This year it’s going to give us enough fruit to feed the entire block. I’ve never seen it this big before.

Tomatoes aren’t doing as well this year as in previous years. Here are the first flowers that will bring the fruit.

One day there were flowers on the eggplant plants. A couple of days later, the fruit begins to appear.

Limon Dance Company – 65th Anniversary Season

Limon Dance Company – 65th Anniversary Season

June 19, 2012

Joyce Theatre

Limon Dance Company celebrated their 65th Anniversary Season with a diverse program.

The Emperor Jones, a revival of a 1956 piece choreographed by Jose Limon, depicts the decline and fall, and the reflections of a gang leader turned dictator. Seated on an ample throne which sometimes tilts, he is dressed in a military costume with epaulets. In the early moments of the piece, his gang arrives to check him out with choreography and movement reminiscent of West Side Story. In a later sequence, props that resembled bare trees, or maybe even prison bars were used to good effect, each one concealing two men. Compelling compositions were created as limbs and bodies unfurled and then hid again. Daniel Fetecua Soto brought swagger and strong but understated emotion to the role of The Emperor. Plodding through his own nightmare, he alternately seems defiant, resigned and haunted, a perpetrator and victim of violence. I was especially affected by the heavy movement in a scene evoking a chain gang which winds up absorbing The Emperor.

Roxane D’Orlenas Juste danced Limon’s classic Chaconne. The spare and elegant movement tends toward the stately and reserved, but as the music soars, the dancer seems to nearly break free of the formal framework, often in sequences of travelling turns, only to return to it again.

I loved the searching looks and fluid rolling movement of Jiri Kylian’s La Cathedrale Engloutie set to the sound of crashing waves against Debussy’s haunting piano chords. As the partners move toward each other, then drift away and come back together, I could almost feel the wave-like rocking of the ocean. The small movement of the feet also reminded me of water lapping against the beach.

Come With Me, choreographed by Rodrigo Pederneiras to the music of Paquito D’Rivera, received its world premiere. In a series of vignettes, the dance focused almost exclusively on footwork — upper bodies tended to stay still and arms rarely rose to shoulder level. Some passages in the choreography almost reminded me of a sailor’s hornpipe. The choreography and movement was very musical. This playful piece seemed to be a favorite among the dancers, especially the women whose smiles were beaming from beginning to end. Despite the reserve of the upper body, the Latin flavor of the piece comes through in the festive costumes and the swooping synchronized partnering.

American Ballet Theatre’s Onegin

Onegin

American Ballet Theatre

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

A few weeks ago at American Ballet Theatre’s Works and Process at the Guggenheim, I heard Reid Anderson discuss his work with John Cranko. Then he took the audience through the staging of the Book Pas de Deux from Cranko’s Onegin. Before the evening was over, I wanted very much to see ABT’s new production of this ballet. It was wonderful to have been given some insight into the process and into Cranko’s intent beforehand, and to be able to take that along with me into the theatre as I was introduced to the full length ballet.

Julie Kent personified Tatiana. In Act I, she is the very image of bookish innocence as she approaches the dark exotic stranger Onegin, played by Roberto Bolle. From the moment that the two begin to dance together, my heart ached from the trusting expression of young love that Kent brought to Tatiana, as well as the weary indifference with which it was met by Bolle’s Onegin.

Bolle is costumed in black, and his movement is every bit as dark, evoking Onegin’s boredom and self absorption. The only moments in which we see a spark of humanity in Onegin are in his own variations, where he seems to be searching for something outside of himself that will relieve him of his jaded view of the world. When Tatiana shows him her book, Bolle turns up the cruelty by sharing a mocking look with the audience that she can’t see. As he dances with Tatiana, there are moments where he is almost dragging his own weight from the heaviness with which Onegin seems to experience life. Bolle was so convincing in the role. Throughout the evening I grew more and more exasperated with Onegin (the character), to the point where I was all but swearing under my breath by the end of Act II.

Every bit as compelling as the two lead characters, were the two secondary leads, Onegin’s friend Lensky and Tatiana’s sister Olga. Jared Matthews and Maria Riccetto were the very image of happy young carefree lovers. Their exuberance was shown in their sparkling facial expressions, their musicality, and the lilting lyrical way in which they moved together in the pas de deux. The lively dance of the villagers seems to pick up on this carefree love, and winds up with an electrifying series of grand jete lifts along the diagonals.

Later, among the lovely silvery turquoise sets that make up Tatiana’s moonlit bedroom, Nancy Raffa, as the nurse, was really cute as she checked on Tatiana, moving a few steps away from the girl’s bed, freezing and peering back over her shoulder, then moving forward and peeking again. I half expected her to go to Tatiana’s desk and read the love letter she’d just written to Onegin.

Again Kent’s Tatiana is all sweetness and innocence as she sweeps through her bedroom, barely able to contain the feelings in her heart. In the lovely Mirror Pas de Deux, as the Onegin of Tatiana’s dream, Bolle transforms into the romantic hero, his focus now trained on the woman in his arms. Julie Kent’s depiction of Tatiana’s innocent love given so freely nearly drove me to tears. She seems feathery and angelic, especially as she stands straight and Bolle lifts her, his arm fully extended overhead, so that she appears like a love struck spirit floating through the room. The partnering is dramatic, with Onegin throwing Tatiana as if she was weightless in her dreaminess, and Tatiana often gliding into a swan-ish landing on one knee with her other leg extended behind her. Kent and Bolle moved together as kindred spirits.

Act II opens with another merry dance performed by the villagers, which includes a series of festive cabriole lifts. Those who danced the character roles, including Martine van Hamel as Tatiana’s mother, provided some good humored comic relief. Bolle’s Onegin, no longer the imaginary hero of Tatiana’s dream, now seems darker still, heartless, annoyed and ultimately cruel. He has no interest in Tatiana and he doesn’t even want to look at her as they dance together. While all the villagers are dressed in earthy country prints and seem to pulse with life, the conflict between Onegin and Tatiana provides a stark contrast, as she is costumed in white and he in black. Onegin has broken Tatiana’s heart and done nothing to spare her feelings. As Tatiana’s mother spirits her away and guides her to dance with the Prince, played by Roman Zhurbin, Julie Kent casts one last heart rending look at the bored Onegin.

Jared Matthews so beautifully descends into hurt and outrage as Onegin and Olga set to teasing Lensky. He brought such strong heartbreaking emotion to the role. Throughout the scene, tension builds and builds, ultimately exploding as Lensky challenges Onegin to a duel. In his last variation, Matthews’ dancing gave clear voice to Lensky’s introspection, anguish, resolve and desperation. He created movement that seemed every bit as searching and bleak as the haunting sets of bare trees of the winter forest.

As an older man in Act III, Onegin returns to St. Petersburg years later, where the prince is hosting a ball. Onegin is still the same bored, jaded individual and Bolle moves with a distinct lack of purpose, his focus never on the woman with whom he’s dancing. His movement really captures the futility that has worn on Onegin, not only through his youth but now weighing even more heavily on him as he settles into middle age. Julie Kent’s Tatiana is now regal and self assured as she dances with the Prince, never even knowing of Onegin’s presence or of the fact that he’s become smitten with her and has begun to figure out that she’s the young woman whose heart he’d broken years earlier. They are introduced for a brief moment, and Tatiana is cordial, but then she goes on her way with the prince, but not before casting one last look of disbelief at Onegin. I felt that throughout the ballet, these subtle looks either cast over the shoulder from one character to another, or shared with the audience, formed crisp clear snapshots which spoke volumes of that moment of the story. In a chilling scene, Onegin stands before the scrim and watches as his time with Tatiana passes before his eyes, culminating with his assassination of Lensky. Bolle, still dressed in black under a harsh white spotlight, moves stiffly. His Onegin seems to struggle for balance on flat feet, looking haunted and stunned with regret over the people and times whom he’d never appreciated before.

The closing pas de deux is especially moving, giving voice to complex emotions that we don’t often see in classical ballet. Julie Kent’s dancing alternately brings out the enduring hurt and anguish that Tatiana had suffered from Onegin’s rejection, as well as her determination to send him away, as well as the little bit of aching love that remained for him in her heart. Kent moves seamlessly from one expression to the next, conjuring a gamut of conflicting feelings. Bolle partners her effortlessly, portraying Onegin’s regret and his new passion, making him seem as human and alive as he had been in the Mirror Pas de Deux. In terms of the story, it made me wonder how he’d conduct his life after that moment. Would Tatiana’s rejection toughen his hide and make him even more jaded, or, having seen what he lost with her, would he set out to try to find it again elsewhere?

Everything about this new production is very well done. The atmospheric sets are lovely and haunting. The ensemble dances are so lively and joyous and the beautiful work of the four dancers who played the lead characters took us through such a wide sweep of intense complicated emotions.